Living with glaucoma: the functional issues

With Glaucoma New Zealand’s annual public awareness campaign ‘Eye Believe’ running in conjunction with World Glaucoma Week (6-12 March) this month, low vision consultant Naomi Meltzer shares some insight about this silent thief of sight.

The focus on glaucoma for eye care professionals (ECPs) has always been on detection, prevention, and treatment. We regard our treatment as successful if the patient retains their acuity and their visual fields remain stable over a period of time. As long as we can maintain this, we assume all is well and the patient will continue to function visually as they have always done. We assume that reading and other tasks that require detailed central vision will remain unaffected. Job done!

The reality is that there are subtle changes that take place beyond the normal ageing process which are common to all neurological and optic nerve conditions, including glaucoma. These changes may include reduced contrast sensitivity, increased glare sensitivity and reduced dark adaptation. The effect can vary from scarcely noticeable to quite disabling.

Contrast sensitivity: the importance of light

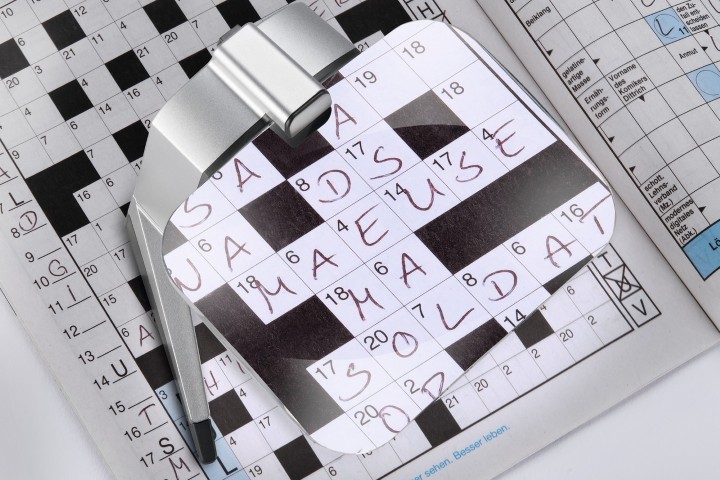

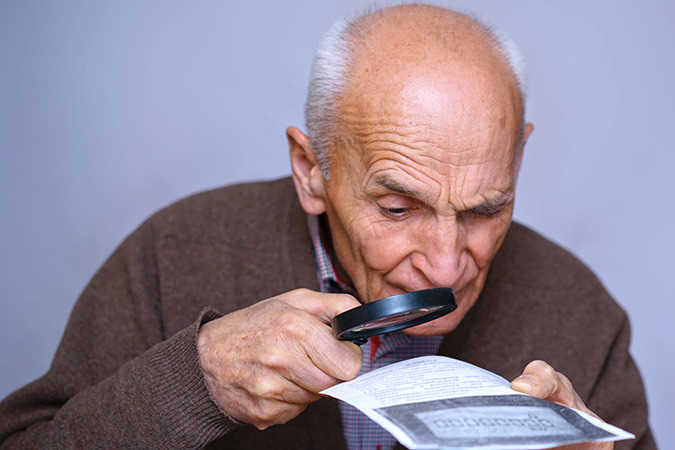

The reduction in contrast sensitivity beyond that which is expected from normal ageing will often have a bigger effect on reading ability than magnification. Every optometrist dreads the patient who returns repeatedly complaining their reading glasses are no good, or the new patient who empties a bagful of spectacles onto the desk and complains at the money they have wasted going from one practice to another looking for a “good one” that can solve their problem. No amount of tweaking the add or the cylinder axis is going to solve the problem if there is a significant loss of contrast sensitivity.

Years ago, I tried to launch an awareness campaign called ‘Make It Readable’. The idea was to show companies that paying good money to produce lousy print which could not be read by their target market, was not very smart. Sadly, nobody was interested. It seems that as long as it looks pretty on the screen, the youthful designer gets paid and all is well. Except it isn’t, because the end result is often so unreadable that it causes frustration even for those with normal vision. For those with loss of contrast sensitivity there is a real and debilitating loss of visual function.

To enhance contrast, we need to add more light. We all need more light as we get older, but with a loss of contrast, light becomes a far more important compensatory tool. The best way to increase contrast is by placing a lamp close to the task so that the light is directed onto the area to be seen. Modern LED lamps are a great improvement over the very yellow and heat-emitting halogen lights. Incandescent lights are still found in many homes but are not energy efficient and generally do not have the ability to change the intensity of the light in the way that many modern LED lamps do.

Internally lit devices such as computers, telephones or e-readers also give enhanced contrast, which makes it much easier to read providing the material downloaded is of good contrast or the device has a setting to enhance the contrast. Unfortunately, we can only read material on a device if it can be downloaded, which is not the same as being able to pick up something and read it independently. That is where electronic magnifiers which convert low contrast or coloured print to high contrast become very useful. A patient who is operating on a very small area of foveal vision, having lost extensive areas of peripheral vision, is not going to thank you for adding magnification which projects the image outside that foveal area. Maximal enhancement of contrast will give them the best chance of using what functional vision they have. Believe it or not, it is not all about size!

We can also use contrasting colours and backgrounds to highlight details, for example, using a contrasting strip of paint or tape to highlight the edge of a step will make it easier to see and therefore safer.

Glare sensitivity

People with glaucoma are often extra sensitive to glare, preferring to turn off lights and pull down their blinds for extra comfort or wearing dark sunglasses which not only cut out glare but also the light that is required to see with!

The answer is to have control of the light, directing it onto the task at hand and not reflecting it back directly into the eyes of the user. Using reverse contrast on devices to reduce background glare can be more comfortable for some. Polarised lenses with lighter tints can enhance contrast and cut out the glare without reducing the light getting through as much as a dark lens will. Other suggestions for patients include using directional lamps, torches or internally lit magnifiers, or covering shiny surfaces to reduce glare.

Dark adaptations

Even in the best-managed cases of glaucoma, the ability to adapt to changes in light levels can be slower than normal so your patient’s vision may often appear to be much worse in low-light levels. This is a safety issue and making patients aware of the need to avoid sudden changes of light or working in unsafe light levels is important.

Photochromic lenses which do not change instantly with sudden changes in light intensity may not be the best solution for people struggling with glare sensitivity and loss of dark adaptation. Certainly, the darkening of the lenses with ultraviolet exposure avoids the need to carry two sets of spectacles and having to switch between them with changing light environments, but sometimes other solutions may need to be explored with glaucoma patients.

Patients often experience these functional changes but don’t necessarily understand what is happening or why. They may not even associate it with having glaucoma. I often talk to patients who don’t even realise they have glaucoma. “No, no” they say, “I go to see my doctor regularly and my pressure is fine!” Meanwhile, in front of me is a report listing the diagnosis and the medications they are taking for glaucoma.

There is no simple answer to these issues as every patient is different and will have different needs, wants and degrees of functional deficit, and most of these subtle sight changes can’t be measured on a high contrast distance vision chart or the peripheral vision tests glaucoma sufferers are so familiar with. But when patients feel they are being understood, your help will be invaluable to them.

For more tips on how to help your low vision patients in practice, see: https://eyeonoptics.co.nz/articles/archive/dispensing-matters-helping-low-vision-patients/

Naomi Meltzer has worked in optometry for more than 30 years and runs an independent optometry practice in Auckland specialising in low vision consultancy. She is a regular contributor to NZ Optics.